Goodbyes are hard! As my 33rd birthday came and went yesterday, it was impossible not to reflect on a trying and thrilling and emotional year that was, one that kicked off with a Beer Olympics in the backyard of my friends Chris and Mari, that rode the high of a Celtics championship and which braced for news we knew would eventually come of my grandfather passing. It would hit another crescendo six months later when, in December, I got engaged. The spring was spent touring and agonizing over business schools and potential new home bases that would eventually force us to vacate our apartment of two years, our home city of D.C., and spend more tears, heart-swells, and words of affection than I knew I contained in saying so long and farewell to our friends, who make our lives tick and hum.

All the while, an unexpected bout of COVID just after my grandfather’s passing sent Marianna and I to separate corners of the house to receive meals delivered on trays and laid at the foot of our respective doors (bedroom and office) as Marianna tried and failed to avoid contracting COVID and I soon became the caretaker. As fate would have it, this unforeseen pause in our lives — like the OG COVID lockdown — invited us to consider whether our lives were meeting up to our expectations.

Of course, we had help arriving at this existential self-reflection. My Gramps had just died at 93-year-old (92 and 349 days). He was my last living grandparent, and he was the proud owner of the fullest and most vibrant life I have ever witnessed. Born in Brooklyn in 1930, his first adventure about the world came at 18 years old, as he and his two cousins set sail in 1948 — three Jews voyaging to Europe just three years after World War II. He became the first in his family to visit Europe, which he said made him an interesting person to the people around him, most of whom had never traveled internationally.

His trip — which began on a 3-tier liberty ship adorned with young people and hammocks and a woman he remembered singing "La Mer" — set sail from New York on a 10-day journey that landed him in Plymouth, England for a nearly four month trip between June and September — one that would take him to the Netherlands, France, Monaco, Italy, Switzerland, and beyond, all on a 3-speed bike he bought in London. The trip was enchanting for him — so much so that he would recount colorful details to me over the phone just before his 90th birthday in hours-long conversations that I recorded and transcribed for posterity — details like the Italian clothing merchant from Milan, Mr. Finzi, whose butler greeted my Gramps and his cousins in a white mandarin-collared jacket and striped green and black pants at the door for a receiving line and a lunch to follow with his assorted guests who adamantly insisted that they were imprisoned by the Nazis — surely an attempt by the guests to ingratiate themselves to my Jewish grandfather since Americans had quickly and ubiquitously become revered in Europe after the war.

He recounted other details like the passage he secured back to the States on an immigrant boat from the Netherlands to Canada, on which the Dutch passengers were still in wooden shoes that clomped on the deck, and where they would pass the time by playing checkers and fashioning the on-board cutlery into metal art. He arrived back stateside with "a wanderlust that never ceased," so naturally, he enlisted in the U.S. Army and shortly thereafter shipped off to Japan and Korea to serve during the Korean War just 6 years after his big Euro-trip. The week he died, we surfaced not only his beautiful old U.S. passports littered with stamps from the world over but also a series of letters his parents had stashed away in an old shoe box, replete with a near-weekly first-hand accounting of his service-time, from basic training at Fort Benjamin Harrison in Indianapolis, to a pre-assignment station in Tacoma, Washington, and eventually on assignment on Camp Drake just outside of Tokyo, and then Yeongdeungpo on the outskirts of Seoul.

His Eurotrip and his service-time — which he reassuringly but sincerely told his parents just before being deployed "will provide many interesting and thrilling experiences, ones that I ordinarily wouldn’t achieve in the routine of civilian life" — these were just appetizers to a life of travel and adventure that would bring him (among so many other places) to India with his son, my uncle (and namesake) Jonathan; Gombe National Park in Tanzania with Jane Goodall, his partner Doris, and 8 others on a chimpanzee expedition; and more than 4 months spent aboard a ship for a Semester at Sea in his late 70s, where he and Doris were guest lecturers, lifetime learners, and cross-generational friends.

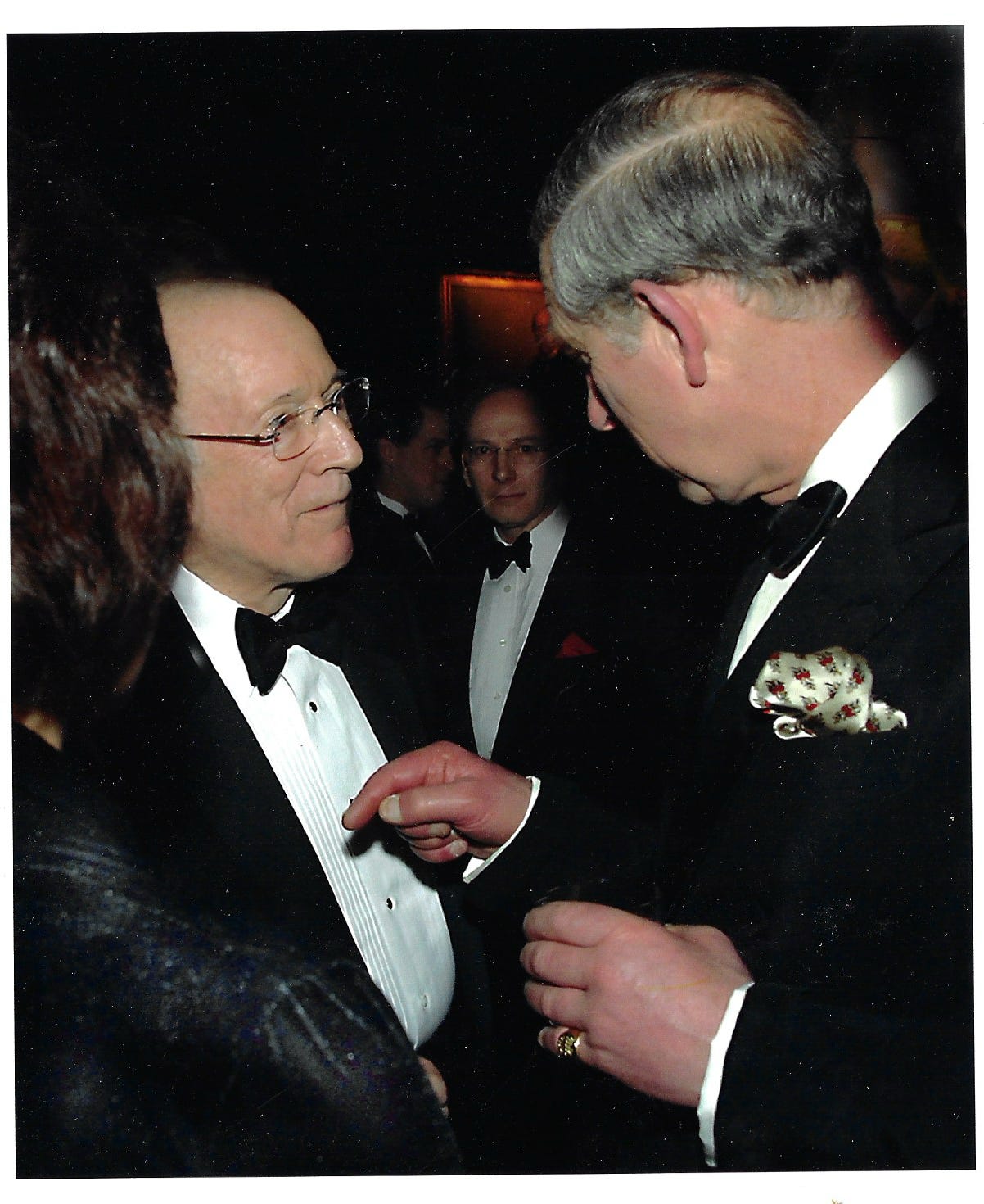

In a life so filled with adventure, it became hard to parse his sensational embellishments from the absolute truth in his later years. This came into stark relief when he would brag about being close friends with Queen Elizabeth II — which we knew wasn’t true — only for us to then stumble upon photos of him in conversation with now-King Charles III and Queen Consort Camilla, somehow imbuing his foggy recollection with kernels of remarkable reality. These discoveries all but validated his penchant for being what he called “star crazy.” He would tell tales of chance encounters with Ingrid Bergman and Charlton Heston and Grace Kelly and Jerry Lewis, which were of course further supplemented by photos with Bill Clinton and Pierce Brosnan, and a folkloric encounter at breakfast one day between a starstruck 3-year-old me and someone my Gramps happened to know — fucking Raffi (!!) — who I refused to talk to because it was too much for me to handle (“Raffi, sir, I love your work”).

It took the moment of pause that I was gifted through a third bout of COVID coupled with my grandfather’s passing to access the rare moments of silence that helped me reckon with this inflection point. It led me to actualize what I suppose I always assumed I would eventually get to in my life: a grand and winding adventure around the world without the time constraints the life forces your way with work and kids and a lease or a mortgage or pets.

And so we got to hatching big plans. Our fanciful, months-long itinerary around the world was at first (and more than just at first) met with a “mhmm, I’m sure you’ll do that” skepticism by nearly everyone. And I don’t blame them — so often in life, we dream big and then we trim our wild, overgrown hedges into something neater and more digestible. Just as often, life gets in the way. But these were not sails we wanted to trim, and if life is a series of opportunities and luck and hardship and maybes and almosts, this harebrained scheme was designed to indict modesty and threaten grief itself with its sheer ambition.

I’ve pondered whether this grand pursuit is more of my grief, spilt over. But then I remember that never in his life did my Gramps seek to be mourned. He was joy and optimism incarnate. He is a vessel for so much of the inspiration of our forthcoming trip but I am hardly chasing after him or the past. I hope this trip can be a conversation with the past and the future and with myself and with the world.

But in departing, if only for a few months, I can’t help but feel a shirked sense of obligation to be a meaningful participant and an active citizen amidst this fraught moment in the life of our country, and I am just as uneasy with the uncertainty around what kind of country we'll be arriving back to when we next touch U.S. soil in early September. My anxieties of course cascade down from the political to the personal, begging questions not just about what our country might look like in a short few months but who I might be when I return.

Every time I end a chapter of my life, I do so knowing it's an opportunity for reform and rebirth — a chance to throw away versions or qualities in myself that I've grown to dislike or know need to change, a chance to embrace what I like in the people I admire, and a chance to redefine my life around a new set of values and priorities, not whole-cloth, but around the margins. I know life to be a constant battle against passivity and resignation and resentment and a fight for hope and understanding and self-actualization.

Even more primordially, we all have a responsibility to refine what we inherited from our parents so that what we pass along to our children is easier to digest and less baggage to sort through before you can arrive at the fruits of life. In my last chapter — moving from New Hampshire to D.C. — I wanted to deprioritize what Derek Thompson calls “the Religion of Workism” or ‘work as religion’ in his book "On Work" in favor of finding and deepening community, reacquainting myself with long-lost hobby activities, enjoying the spoils of living in a big city for the first time since college, and finding someone I wanted to spend the rest of my life with.

In my next chapter, my goals are less tangible and more cerebral — to continue the enjoyable work of building and folding into and maintaining rich community, and leaving behind what is probably too much time spent on my phone — a passive act which, among other things, wastes my precious time and deepens my sense of anger and dread at the direction of the world without doing much to enrich my life. I hope I can leave behind, by way of fulfillment of some big goals, a pervasive sense I've always had that I assume troubles even the most successful people — the nagging feeling that I need to do more to ensure I am making the most of my one life.

What will the next few months hold? We shall see. The story is yet to be written, but it will be written here on this Substack that I’m transforming into a travel blog, in which I’ll report many things you might find too mundane to print, or awkwardly phrased in haste so that I can live in the moment while keeping a record for friends, family, and posterity.

I know the trip will have ups and downs, joy and frustration, things that go as planned and things that don't, a mix of adherence to an itinerary and spontaneity, ways in which our plans fall short of our expectations and happy accidents that exceed our wildest imagination for what this trip could be. I hope we have left enough room for the happy accidents, and for life in its essence to seep through the cracks. I hope we have done enough planning so that we can permit ourselves to be immersed in all the grand events we have concocted.

If this isn’t indulgent enough by itself, I have one more ambition for this journey. I hope our trip also serves — like my Gramps’s wanderlust-inducing extravaganza — to inspire my children or grandchildren to endeavor on the same kind of journey themselves. If nothing else, I hope to at least internalize the lessons we've gleaned from simply conjuring up the journey — that life is a precious and finite resource and how you spend it matters; that it should be done not with obtuse caution but great care, not with freneticism or chaos but unbridled joy snd whimsy and poetic reckless abandon.

And for the many, many goodbyes and see ya laters we’ve said to friends and family in D.C. and Chicago and The Berkshires and Vermont and Boston, I’ll say it once more with the sentimentality that’s swelling in me even now: I love you all and miss each of you already more than you can imagine. I can’t wait to live more life alongside all of those reading this and plenty more who never will read it.

Until then, I couldn’t imagine a Father’s Day gift that might tickle my Gramps more than to let him know that we take off tomorrow morning for Japan.

Reading this through tears. 🥲 beautifully said, and we cannot wait to read about all of your travels. Best wishes during this new phase of life 🩷